The History of the Tuba

|

The tuba, as we all know, is a big instrument. The subject of the tuba, as it turns out, is even bigger. It all begins with a peculiar-looking Mediaeval instrument made of wood and leather that was redesigned a number of times, first gaining keys, a straightened wood or metal body in two sections and even more keys, an upright configuration of graceful, wound tubing and valves, a circular design resembling a snake once more, and eventually culminating in the 4-valve BB flat compensating behemoth we all know and love today.

The tuba is an instrument for which there was a demand long before its creation. Various inventors sought to fill the desire of composers, bandmasters and orchestra conductors for an instrument that could supply the bottom end, especially in the days when orchestras were growing exponentially in size. Hector Berlioz’ remarks concerning the serpent and ophicleide are well-documented and uniformly uncomplimentary. To do these instruments justice, however, Wagner, who loved a lush tone-palate, wrote supporting passages for the serpent, and demand for the ophicleide remained such that it lasted until the early 20th century.

Though this researcher can never hope to do justice to this instrument in so short a piece, it nevertheless is my hope that this overview will provide the basis from which to form meaningful direction and questions in the minds of those who wish to know more about this instrument, its origins and related instruments.

The Serpent

|

The serpent was invented in France by Edme Guillaume ca 1590. Though metal versions exist, the original and most predominant materials this instrument was fashioned from was wood covered with leather. The mouthpiece was variously made of wood, bone, ivory, oxhorn, ceramic, and various metal alloys such as brass, bronze and pewter.

The original serpent, coiled back and forth like a snake, was played by means of six holes. Later on, keys were added so that this instrument could play with greater facility.

This instrument saw wide use in the church as a bass accompaniment for religious music that had evolved from Gregorian Chant. The earliest known composers of this form were Leoninus and Perotinus, or Leonin and Perotin, in the 12th century. The composers Leoninus and Perotinus are critically important to us because they are the first two recognised composers of Western Music: for the student of Western Music, it all begins with them.

In Britain, besides its sacred role, the serpent was soon adopted as the bass member of military wind bands.

Down through the centuries, the serpent proved remarkably resilient to sweeping change in instrument design. Though it was redesigned several times and adapted for modern use, the original instrument managed to hang on, and is still with us today, kept alive by various groups and collectors with a keen interest in this venerable old instrument.

Composers like Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Berlioz, Meyerbeer and Wagner were no stranger to the serpent, and even today, composers in search of interesting sounds to compliment their tone-palate, will occasionally score solo parts for this 400-year-old relic.

The largest version of this instrument, the contrabass Anaconda, appeared belatedly in 1840, and is now part of the collection of the Edinburg University Collection of Musical Instruments.

The Ophicleide

|

In 1810, in Dublin Ireland, bugle-maker Joseph Halliday created the keyed bugle, the progenitor of the modern cornet. He based his design upon the keyed trumpet, an instrument that had been around since the late 18th century. In 1821 he created the ophicleide, the name being constructed from the two words “ophis” (Greek for “serpent”) and “kleis” (for “stopper” or “cover”).

Though the ophicleide bears no resemblance to its progenitor, being made of brass, having keys and pads like a saxophone, and standing upright, what matters here is its less obvious internal design. It is a brasswind of conical bore utilizing holes that, when covered or uncovered, change the pitch of the instrument.

If the appearance of the ophicleide is reminiscent of the saxophone, there is good reason for this. The saxophone was but one of several attempts to fuse ophicleide and woodwind design. In fact, Sax’s earliest saxophones were often refered to as the ophicléides á clefs, or the ophicléides á clefs et á bec.

Adolphe Sax was by no means the first inventor to attempt this. Other fusions of ophicleides and woodwinds, with single and double reeds, predate Sax’s efforts. In fact, when he first introduced the progenitor of the modern saxophone at a Paris exhibition, another inventor had brought a very similar instrument. Because Sax’s instrument was far superior to its competitors, the competition was soon routed, but in typical Sax fashion the authenticity of his invention is doubtful.

The ophicleide all but swept aside its predecessor, but the plucky serpent managed to hang on, whilst the ophicleide finally expired in 1928, though it has recently been resurrected, and faithful replicas are once again available.

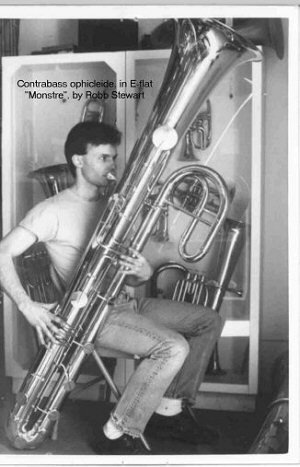

The largest version of the ophicleide is the contrabass Monstre Ophicleide, built by Robb Stewart, an expert at making replicas of 19th century brasswinds.

|

|

The Bass Horn

Another variation on the serpent, the earliest bass horn I am aware of was manufactured circa 1800, predating the ophicleide by about twenty years. I am as yet uncertain as to the origin of this instrument, or who its inventor was, but this early example comes from England.

The Russian Bassoon

The Russian bassoon, despite its name, is actually a Belgian-made instrument of serpent configuration consisting of two wooden tubes joined at the bottom. It was invented circa 1820

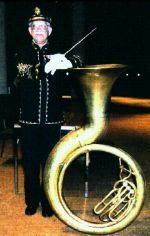

The Helicon

The helicon, thought to have been invented in Russia circa 1845, was designed to be a marching horn, carried on the shoulder. This bass instrument was the forerunner of the Sousaphone, which is the self-same instrument with a directional bell grafted on. In 1850, Ignaz Stowasser of Vienna produced large numbers of these instruments for cavalry and infantry bands.

|

The helicon was very popular across Europe and in the United States.

The Tuba

The tuba proper was first patented by Prussian bandmaster Wilhelm Wieprecht and German instrument-builder Johann Gottfried Moritz in 1835. This instrument was soon adopted by British brass bands.

Tubas come in a number of keys: BB flat, CC, E flat, F, and GG, though the tuba is what is called a “non-transposing” instrument, as its music is read and played in concert pitch.

There are many design configurations for the tuba. The compensating valve design allows the playing of true, pure pedals that are in tune; Miraphone’s tuba, held almost in the transverse position, has four rotary keys; the bell can be forward facing or up; they can have up to five valves, either in-line or with the extra two strategically placed for the left hand; bell diameter can vary from 37-74 cm (15-30 inches); they can be built of brass that is often electroplated with silver, nickel or copper, or they can sometimes have bells of plastic or fibreglass; the bell tubing can we wide and open like a funnel, or relatively small, ending in a large bell.

Though the tuba has a conical bore, its profile is not that of the bass Saxhorns, which are members of the cornet à pistons (cornopean) or valved bugle family. The tuba has a wider conical bore profile and deeper cup mouthpiece.

The original Wieprecht\Moritz instrument, like its Bombardon (helicon) analogue, was an F instrument.

The Bass Saxhorns

|

By 1843, Adolphe Sax had begun manufacturing Wieprecht-Moritz-type tubas in Paris. His work on the tuba, however, was a limited, secondary matter compared to the brasswinds that bear his name. His apparent intent was to create an integrated family that included the entire range of the various diverse brasswinds. To accomplish this he selected a single archetypal design upon which all of his instruments were based. That underlying design is the bore profile of the valved bugle or cornopean, the predecessors of the cornet.

This means that the Eb bass Saxhorn brass instruments have a narrower bore and smaller bell profile than the tuba.

The Sousaphone

|

The Sousaphone, alleged to have been first made by C. G. Conn in 1898, was actually first manufactured by J. W. Pepper in 1893, where it was displayed at the industrial exhibit in Philadelphia that same year.

http://www.jwpepper.com/history/sousa.html

http://members.aol.com/ncpmb/sousaphone.htm

As previously stated, the Sousaphone is really just a helicon with directional bell grafted on. Rather than being made at Sousa’s suggestion, the opposite is actually true- that J. W. Pepper suggested the design to John Philip Sousa. In fact, the original J. W. Pepper Sousaphone is still in existence

The Compensating Valve System

|

The compensating valve system was invented by D. J. Blaikely in 1878. It is designed to extend the range of the instrument, whilst stabilizing the pedals’ pitch. The basis of this principal is that when two or more pistons are used at the same time, the combined length of tubing serves to correctly adjust the pitch. To understand this concept, one must consider that the length of tubing added by opening each piston is not that of a perfect interval. Each interval is actually a bit sharp, which is necessary when it comes to playing an equal-tempered scale. The natural scale, especially of a conical bore instrument, is actually flat, each scale having its own unique arrangements of perfect intervals, such as perfect seconds, thirds, sixths and octaves. While it is not possible to freely modulate while using natural intonation, the sound, called “just intonation,” is absolutely gorgeous.

Victor Mahillon further refined this system circa 1886 with his “automatic regulating pistons” design.

The Wagner Tuba

|

The Wagner tuba comes in two forms- the smaller 4-valve F\B flat horn which has roughly the same range as the Horn and Tenor (alto) horn, and the larger B flat bass horn. The F horn uses a “French” horn mouthpiece, whilst the bass version uses a correspondingly larger mouthpiece. Both can best be described as falling somewhere between a Saxhorn and a “French” horn in bore profile.

The Wagner tuba has a bell with almost no flare, and the entire bore, including though the valves, is conical, which together serve to impair the instrument’s output, which no doubt in turn curtailed this instrument’s chances of gaining widespread popularity.

The smaller F Wagner tuba, like the F contralto trumpet, is still widely popular in Europe, however, but as a staple of small brass ensembles. New improved models of both versions of this horn, of high quality, are today being manufactured by Hoyer, fine makers of “French” horns.

by Gregg Monks

Links

Serpent Photo Gallery

The Ophicleide

The Contrabass Compendium

Meister Hans Hoyer Wagner Tuba

Edinburgh University Collection of Historic Musical Instruments

Edinburgh University Collection of Historic Musical Instruments - Euphoniums and Tubas